The Copper Age

The Sumerians and Chaldeans

Copper first came into use as the earliest non-precious metal employed by the Sumerians and Chaldeans of Mesopotamia, after they had established their thriving cities of Sumer and Accad, Ur, al’Ubaid and others somewhere between 5000 and 6000 years ago. These early people developed considerable skill in fabricating copper and, from these centres, the rudiments of craftsmanship spread to the river-dwelling people of Egypt where it continued to flourish for thousands of years long after their own civilisation had degenerated.

Although the Sumerian art-forms were rather crude, many of the objects they produced were wonderfully life-like. Bronze pots and mixing trays have been found at al’Ubaid, near Ur (circa 2600 BC), also silver ones of the same date, besides silver-spouted bronze jugs, saucers and drinking-vessels which were probably used for ceremonial purposes. Still earlier are some copper chisels and other tools from Ur, likewise copper razors, harpoons, cloak pins and other small articles. Far older than any of these are some copper arrows and quivers, together with prehistoric Sumerian copper spearheads, all of which have successfully survived the test of time.

Even at such an early date, these people adopted the practice of burying under the foundations of buildings a record concerning the builder. Small bronze or copper figurines were likewise buried there at the same time. One such record, in the form of a copper or bronze peg 12 inches long, relates to a king of the First Dynasty at Ur. A more remarkable one shows a god holding a peg about 6 inches long; this came from the temple at Ningursu (circa 2500 BC).

Another proof of the indestructibility of copper is connected with a Sumerian wooden sled, which was intended to run on the sands; it is picturesquely known as ‘The Queen’s Sledge’. This sled was drawn by two oxen wearing large copper collars, while the reins had copper studs. A Sumerian soldier who presumably marched alongside this equipage wore a copper helmet.

(Courtesy of The British Museum)

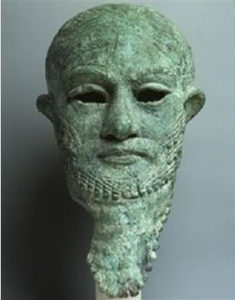

Whilst on the subject of Sumerian copper, it is worth mentioning the bust of Ur-Namma (see photo courtesy of Metropolitan Museum of Art). The casting of the bust in ‘arsenic copper; was a considerable technological accomplishment at the time and its artistic merit is still unrivalled today.

(Courtesy Metropolitan Museum of Art)

The Egyptians

From the earliest dynasties onwards, Egypt developed a very high degree of civilisation, and the exploitation of metals – copper, bronze and precious metals such as gold and silver – was an essential part of their culture. The Egyptians first made considerable improvements over the Mesopotamian technique, and then, apparently being satisfied that they had reached the summit of human excellence, they continued the same practices, century after century, so that only by reference to the king concerned can distinction be made between articles which may differ in age by a thousand years or more. They obtained most of their copper from the Red Sea Hills.

The tombs of the Egyptians have yielded many examples of copper craftwork, including copper plumbing pipe, which is still in good condition today. Their excellent condition today can, to a large extent, be attributed to the dry climate, and our knowledge owes a considerable debt to their practice of burying in the tombs of the important dead, complete equipment for one’s needs in the next world. Thus they had model set-pieces, showing bakehouses, tanneries, brew-houses, boats, all complete with carved wooden human figures and implements which show the actual life of ancient Egypt. With these were buried the real bronze, copper and precious metal objects connected with the deceased. Despite a tremendous amount of plundering by tomb robbers throughout all the ages, much has remained for posterity.

The Egyptian coppersmith must have been a man of importance since he had to make saws, chisels, knives, hoes, adzes, dishes and trays, all out of copper or bronze, for artisans of the many trades. There still exist very serviceable early Egyptian bronze strainers and ladles; likewise tongs, some of which had their ends fashioned into the shape of human hands. Thebes has yielded beautifully preserved bronze sickle blades with very business-like serrated edges. The Egyptians even possessed bronze model bags which were carried by servants at important funerals.

Homer referred to the metal as ‘Chalkos’; the Copper Age is therefore referred to as the Chalcolithic Age. Roman writings refer to copper as ‘aes Cyprium’ since so much of the metal then came from Cyprus.

The Bronze Age

There is evidence that early workers knew that the addition of quantities of tin to copper would result in a much harder substance.

This alloy, bronze, was the first alloy made and found particular favour for cutting implements. Numerous finds have proved the use of both copper and bronze for many purposes before 3000 BC; bronze revolutionised the way man lived.

Some of the earliest bronzes known come from excavations at Sumer, and are of considerable antiquity. At first, the co-smelting of ores of copper and tin would have been either accidental or the outcome of early experimentation to find out what kinds of rock were capable of being smelted. The smelting of lead was known by 3500 BC and lead, tin and arsenic all appear as alloying elements in smelted copper from early dates.

An appreciation of quality in bronze depending on the tin content emerged only slowly. Consistency of composition of bronzes dates back to about 2500 BC at Sumer, with bronzes commonly containing 11-14% tin – reasonable evidence both of technological forethought and the appreciation of metallurgical and founding properties. Indications of bronze production as far back as 2800 BC come from places as far apart as India, Mesopotamia and Egypt, and make a single origin for bronze smelting significantly further back in time a strong possibility.

Trade by land and sea, and the succession of cultures and empires, had dispersed knowledge of the copper-based metals slowly but surely throughout the Old World. By 1500 BC it had spread across Europe and North Africa to the British Isles, and in other directions as far as India and China. Copper, bronze, copper-arsenic, leaded copper, leaded bronze and arsenical tin bronzes were all known by this date in most parts of the Old World.

‘Ötzi’, the 5000 year old mummified man found high in the Alps on the Italian-Austrian border was found with many implements including an excellent arsenical copper axe. The copper axe was hardened by hammering and was much tougher than the stone or flint alternatives. It did not shatter on impact and could be softened by heating and re hardened to maintain its cutting edge. It seems that he was probably a coppersmith himself, since his hair had high concentrations of copper and arsenic, which could probably have come from no other source.

(© South Tyrol Museum of Archaeology)

Alloys containing zinc were also emerging at this time, from Cyprus and Palestine, though the alloying is believed to have been natural in origin, due to the local ore containing some smeltable zinc minerals. Alloys similar to modern gunmetals were being cast before 1000 BC though the proportions of copper, tin, zinc and lead were not well established. Following the emergence of true brasses in Egypt in the first century BC, possibly from Palestine, the industrious and methodical Romans rapidly consolidated the knowledge and usage of copper, bronzes, brasses and gunmetals.

Bell founding originated in China before 1000 BC and in time Chinese bell design attained a high degree of technical sophistication. The technology spread eventually through Asia and Europe to Britain, where early evidence of bell making has been dated to around 1000 AD through excavation of a bell casing pit at Winchester.

Several important books were written during the Middle Ages concerning the extraction, smelting, casting and forging of copper. These established that the casting and working of copper and its alloys had its origins in craft traditions and practices that had developed over several thousand years. How much of this was originally handed down in writing is not known, since it is only from mediaeval times that the written tradition in technology is unbroken. It is through the Christian monastic and Islamic cultural traditions that detailed accounts of these early technologies have survived. The writings of the monk Theophilus in the 11th century, and of Georgius Agricola and Johannes Mathesius in the 16th century, all describe in detail the metal producing technologies of their day. Often these had changed little for centuries.

The output from the Bronze Age mines was considerable – an assessment based on old mine maps and studies of prehistoric workings at Mitterberg in the Austrian Alps indicated that about 20,000 tons of black copper had been produced there over the period of the Bronze Age. Black copper was the usual product of ancient smelting and contained about 90% copper. It was traded as flat cakes weighing a few kilograms for later refining to purer copper by ‘poling’.

Significant engineering uses had been found for copper as early as 2750 BC, when it was being used at Abusir in Egypt for piping water. Copper and bronze were employed for the making of mirrors by most of the Mediterranean civilisations of the Bronze Age period. The obliteration of Carthage by the Romans has obscured developments in Northern Africa at that time. Evidence of the considerable engineering skills of the Carthaginians has emerged, including the earliest known use of gear wheels, cast in bronze.

Bronze was used in many of the artefacts of every day Roman life – cutlery, needles, jewellery, containers, ornaments, coinage, knives, razors, tools, musical instruments and weapons of war. This pattern of use tended to be repeated wherever the smelting of bronze and copper was introduced, though necessarily on different time scales. The New World and Africa lagged in these developments by 3000-3500 years because of the distance and isolation of these areas from the trade routes that loosely bound the ancient world.

Middle Ages and Beyond

Printing

The invention of printing in the 15th century increased the demand for copper because of the ease with which copper sheets could be engraved or etched for use as printing plates.

A copper plate created by either of these methods will produce a finer and more delicate print than the previously used wooden blocks. Images of this kind from copper plates are separate from the text. They have to be bound into the finished book, acquiring the name of ‘plates’. From the late 16th century a volume with plates becomes the standard form of illustrated book.

At this time copper plates were adopted as the best means of engraving maps. The first known maps printed from copper plates are two Italian editions, dated 1472, by the geographer Claudius Ptolemy. From 1801, both HM Ordnance Survey and the Admiralty used copper plates for printing maps and charts.

Increasingly modern methods use chemical etching on copperplate in the pre-press process providing for less restrictive more creative designs.

More information on copper plate printing

Sheathing

Copper had other important uses at sea, as copper sheathing of the hulls of wooden ships was introduced in the middle of the 18th century. This was intended to protect the wood against attack by the Teredo shipworm when in warm seas. It was found that it also kept the hulls free of barnacles and other marine growth, preventing the consequent severe drag that slowed the ships. This enabled Nelson’s ships to spend many months on blockade duty and still be swift when battles commenced. Now, copper-nickel cladding can be applied to wood, polymer or steel hulls to allow ships to operate at higher speeds.

More information on copper sheathing in the navy

UK Production

In the early 18th century, Swansea was becoming a major copper centre and by 1860 was smelting about 90% of the world’s output. At first, Swansea obtained most of its ore from many mines in Cornwall and Anglesey. By 1900, Morwelham on the River Tamar was the world’s largest copper port and Parys Mountain near Amlych in Anglesey was the world’s largest copper mine. As the industry developed and other sources were found abroad, almost all ores were imported. The smelting of the ores subsequently moved nearer the sources of supply.

Copper and tin mining had begun in Cornwall in the early Bronze Age (approximately 2150 BC) and the copper production peaked in 1856 with 164,000 tons being produced. Tin mining continued until 1998. Neither tin nor copper are produced in Cornwall today.

(Courtesy Cornwall Centre, Redruth)

During the 19th century, Birmingham became the main centre for fabricating non-ferrous metals in Britain, a position that is still held. Many major developments in the copper industry emanated from the Birmingham area.

- In 1832 George Muntz patented a process for the manufacture of brass consisting of 60% copper and 40% zinc. View Muntz’s specification (Courtesy of Patents Collection of Sheffield Libraries).

- A method for the application of electrolysis to the refining of crude copper was invented by a Birmingham silver-plater, James Elkington, in 1864 and led to the establishment of the first such plant in Swansea in 1869.

- Towards the end of the 19th century, Alexander Dick introduced the fundamental new process of hot extrusion for making brass rod from billet.

Copper and Communications

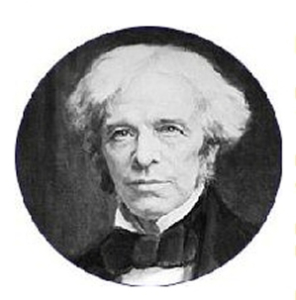

By far the greatest extension in the use of copper resulted from Michael Faraday’s discovery of electromagnetic induction in 1831 and the subsequent development of the electrical engineering industry, including the invention of the electrical telegraph in the early nineteenth century, which involved sending electrical signals along copper wire. It was possible for the first time to transmit almost instant messages across continents and under oceans with widespread social and economic impacts.

The telegraph revolutionised communications which had previously relied on smoke signals, pony express, beacons, flag semaphore, heliograph (mirrors) and pigeon post.

The world’s first commercial telegraph service was established by the Electric Telegraph Company in England in 1846; this company being the forerunner of the modern BT. This invention has been compared in its impact on society to the modern day internet. The electric telegraph system survived until 2006 (Western Union, USA) and 2013 (India, State owned telecom).

The next significant stage came with voice transmission (telephone) along copper cables, patented in 1876 by the Edinburgh born Alexander Graham Bell.

An important historical event took place in 1929 when the first transoceanic music broadcast by telephone from Europe to the USA occurred.

In the 1980s came the fax revolution, followed by the internet, satellite communication and increased use of optical fibre. Whilst the use of copper has been affected by the increased use of optical fibre, it is far from becoming obsolete since it is used in some form in all of these modern technologies.

Today, modern society demands that data passes between people and organisations in milliseconds. Large diameter submarine copper cables transfer signals between continents, while tiny copper wires transmit power and data to individual users. Even wireless communications require copper cabling in masts and relay stations.

From the early days to modern times, copper cables and wire are the unsung heroes of the age of communication, which is a rapidly evolving industry.

Who knows what the next few years will bring?

The History of Brass

Brass has been made for almost as many centuries as copper but has only in the last millenium been appreciated as an engineering alloy used to make mass produced goods and as an alloy capable of being formed by working or casting, finished by embossing, engraving and piercing and joined by soldering and brazing into exquisite objects of the finest artistic calibre.

Initially, bronze was easier to make using native copper and tin and was ideal for the manufacture of utensils. While tin was readily available for the manufacture of bronze, brass was little used except where its golden colour was required. The Greeks knew brass as ‘oreichalcos’, a brilliant and white copper.

Several Roman writers refer to brass, calling it ‘Aurichalum’. It was used for the production of sesterces and many Romans also liked it, especially for the production of golden coloured helmets. They used grades containing from 11 to 28% of zinc to obtain decorative colours for all types of ornamental jewellery. For the most ornate work, the metal had to be very ductile and the composition preferred was 18%, nearly that of the 80/20 gilding metal still in demand.

Before the 18th century, zinc metal could not be made since it melts at 420oC and boils at about 950oC, below the temperature needed to reduce zinc oxide with charcoal. In the absence of native zinc, it was necessary to make brass by mixing ground smithsonite ore (calamine) with copper and heating the mixture in a crucible. The heat was sufficient to reduce the ore to metallic state but not melt the copper. The vapour from the zinc permeated the copper to form brass, which could then be melted to give a uniform alloy.

(© Victoria and Albert Museum, London)

In Mediaeval times there was still no source of pure zinc. When Swansea, in South Wales, was effectively the centre of the world’s copper industry, brass was made from calamine found in the Mendip hills in Somerset. Brass was popular for church monuments, thin plates being let in to stone floors and inscribed to commemorate the dead. These usually contained 23-29% zinc, frequently with small quantities of lead and tin as well. On occasions, some were recycled by being turned over and re-cut.

One of the principal industrial users of brass was the woollen trade, on which prosperity depended prior to the industrial revolution. In Shakespearean times, one company had a monopoly on the making of brass wire in England. This caused significant quantities to be smuggled in from Mainland Europe. Later the pin trade became very important, about 15-20% of zinc was usual with low lead and tin to permit trouble-free cold working to size. Because of its ease of manufacture, machining and corrosion resistance, brass also became the standard alloy from which were made all accurate instruments such as clocks, watches and navigational aids.

The Longitude Problem: John Harrison (1693-1776)

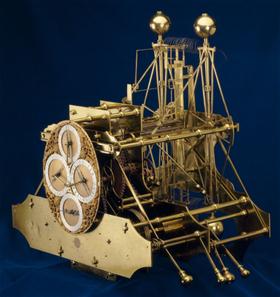

John Harrison, a Yorkshireman and inventive genius clockmaker, solved the problem of determining longitude at sea, a problem that had baffled scientists for centuries. Many lives had been lost at sea due to an inability of a ship’s captain to know his exact location.

Over many years (1728-1770) he constructed five sea clocks and watches, mainly in brass, which kept an accurate time of the starting port, Greenwich. By comparing the actual time with the Greenwich time it was possible to accurately find the longitude location. Harrison was justly awarded a prize of £20,000 (£2.5 million) for his work.

With the coming of the industrial revolution, the production of brass became even more important. In 1738, William Champion was able to take out a patent for the production of zinc by distillation from calamine and charcoal. This gave great impetus to brass production in Bristol. Wire was initially produced by hand drawing and plate by stamp mills. Although the first rolling mill in Swansea was installed at Dockwra in 1697, it was not until the mid-19th century that powerful rolling mills were generally introduced. The Dockwra works specialised in the manufacture of brass pins, the starting stock being a plate weighing about 30kg. This was cut into strips, stretched on a water-powered rolling mill and given periodic interstage anneals until suitable for wire drawing.

With the invention of 60/40 brass by Muntz in 1832, it became possible to make cheap, hot workable brass plates. These supplanted the use of copper for the sheathing of wooden ships to prevent the attachment of marine organisms and worm attack. An example of brass sheathing was the Cutty Sark launched in 1869. The Muntz metal was about two thirds the cost of copper and had identical properties to copper for this application. Muntz made his fortune.

With improvements in water communications, the centre of the trade moved to Birmingham to be nearer to fuel supplies and to facilitate central distribution round the country. With the invention of the extrusion press in 1894, Alexander Dick revolutionised the production of good quality cheap rods.

Subsequent developments in production technology have kept pace with customers’ demands for better, consistent quality in larger quantities. The brass now is cast to extrusion billet form in three-strand horizontal continuous casting machines, cut to length, reheated and extruded in modern presses designed to give high quality and minimum wastage. Subsequent straightening, drawing, annealing, cutting to length, pointing and inspection is carried out under approved quality management schemes that ensure material is supplied as ordered.

Today, brass is the best material from which to manufacture many components because of its unique combination of properties. Good strength and ductility are combined with excellent corrosion resistance, attractive colour and superb machinability.

The valuable properties of copper which were evident at the dawn of civilisation were an attractive colour, excellent ductility and malleability and were capable of being hardened by working. In modern times, further properties have been appreciated and exploited across a wide range of applications; high thermal and electrical conductivities, excellent corrosion resistance, low attachment of marine organisms and hygienic properties.

In the 21st century, copper and copper alloys make a significant contribution to the latest developments in renewable energy, information and communication technology, coinage, architecture, transport, sea water systems, health and sanitation.

-----

Last update: June 14, 2021

Comments

0 comments

Article is closed for comments.